Journey photo album

Challenging the temperature scale in the harshest climates on Earth

Journey photo album

Interpretation of the logger’s graph (using LogTag Analyzer 3 software)

First day (August 11)

It is the single day when I’ve spent significant time nearby the measuring equipment. During the hike towards the bottom of the depression the sky was completely clear, the wind (easterly) light to moderate and these conditions continued also afterwards the entire day. The data logger started the continuous measurements at 12:42 PM, the first reading was 36.6 degrees Celsius. As I set the device for 2 minutes logging (short intervals) the curve has the typical “saw aspect” with many small ups and downs inside the general “big waves”.

Generally, the temperature was constantly rising until 4:48 PM, when the maximum of 40.1 degrees Celsius was reached. I was present, waiting in a camping chair at that time and observed little to no wind near the tripod in the hottest part of the afternoon. The obvious drop started after 7:30 PM and continued to 11:30 PM when the temperature reached 29.0 C. After that the curve became irregular, reaching the night’s minimum shortly before midnight (28.9 C), later climbing back to 31.6 C. As there were no clouds (I saw the starry sky through the transparent mesh of the mosquito tent), the disturbance was certainly caused by the wind. In the final part of the night, before leaving, I checked again the device and observed 29.9 C at 5:10 AM.

Second day (August 12)

The bulk of this day I’ve spent in Aktau after reaching the city around 11:30 AM, hitchhiking from the Zhanaözen road, north-east from the depression. The completely clear conditions continued, in the afternoon it was markedly hot even near the sea.

The graph shows a very regular diagram during the entire day, the temperature continuously climbed until it reached the maximum (40.6 degrees Celsius) at 3:32 PM, which is also the highest value of the entire measuring period. The earlier peak (maybe) could be attributed to the fact that the wind wasn’t dominantly easterly in the afternoon and the sea breeze could have slightly moderated the farther rise in the mid afternoon.

The obvious drop started again around 7:30 PM and lasted until 11:10 PM, when 28.7 C was reached. A very similar pattern with the previous day & night combo, complemented also with the following irregularity (certainly wind again). The main difference is that this time the minimum went down to 24.5 C in the early morning (5:52 AM).

Third day (August 13)

Today I left Aktau and travelled by train to Shetpe town, where I visited the inselberg named Ayrakty. I reached the area after 3 PM and saw no clouds in the sky during the entire day. In the afternoon I observed 38-39 C (hand measurement) around 70-80 m elevation. The wind was light until the evening (even on the elevated plateau), however in the night became consistently stronger. The sky remained clear.

Likely because the wind became again south-easterly, the maximum (40.6 degrees Celsius for the second time, equaling the previous record) was reached at 4:52 PM, very similar with the first day’s case. The obvious drop now started around 8 PM and except a short disturbance period between 10-11 PM continued pretty constant until the morning (7:02 AM), when reached the minimum of 26.3 C.

Fourth day (August 14)

Starting in the night, this day was a windy one and slightly less hot than the previous three, which were very alike. I hiked in the surroundings of Shetpe (Ayrakty and Sherkala) and observed almost no clouds. In the early afternoon I moved closer to Aktau to the so called “km 43” beach, where the sky became partly cloudy.

The day part of the graph looks quite regular again, reaching the maximum of 38.1 degrees Celsius at 3:50 and 3:58 PM. However, the obvious drop started much sooner this time (sea breeze?), around 5:45 PM and lasted until 9:10 PM, when reached 30.0 degrees. From here the curve is more irregular (I suspect wind again), but generally was descending until the morning, when reached 24.5 C at 6:54 AM.

Fifth day (August 15)

Sleeping on the beach, I continued the hike in the morning towards the road, where I hitchhiked back to Aktau before noon. It was mostly sunny with scattered altocumulus clouds in the city, the temperature less hot than before. The wind was much lighter than yesterday in the Sherkala area.

The daily graph looks normal again, reaching the peak of 36.0 degrees Celsius at 3:54 PM, which is the “weakest” maximum of the entire measuring period. The obvious drop started around 6:45 PM this time and was clean until around 10 PM, when reached 28.0 C. Then the descend became less regular with some abrupt ups and downs during the night, though the general tendency was evidently downwards. The minimum happened at 5:52 AM in the morning and was much lower than the previous ones: 19.3 degrees Celsius.

Sixth day (August 16)

Today I went back to collect the measuring equipment, this time starting the hike from the Kuryk road, situated on the other side of the depression (south-west). In the early afternoon I’ve crossed the entire salt pan transversely, before reaching the weather station. There were some scattered clouds, but overall much more sun than shade. I stopped the logger at 6:40 PM when the screen showed 33.9 degrees Celsius. In this later part of the afternoon I observed some convective rain clouds in the south, south-east, probably between the sea and the basin.

The graph of this day is also pretty regular, but can be discerned a little “rush” as the maximum of 36.4 degrees Celsius was reached sooner than usual: 3:06 PM. I attribute this fact again to the changing wind directions (namely the sea breeze), which started to counteract the afternoon heat.

The average maximum temperature of the six day measuring period is 38.6 C, while the average minimum of the related five nights is 24.7 C, giving a mean amplitude of 13.9 degrees Celsius. This combo is above the level of the hottest places of Europe for the month of July, closer to the Karakum desert in Turkmenistan or south-eastern Turkey around the Syrian border. Though this could not be considered a fixed generality as this summer was hotter on average in many places, especially in the mediterranean basin.

General conclusions

Comparison with the weather station of Aktau

Situated near the coast, Aktau receives the moderating effect of the Caspian Sea, thus the maximum temps are generally a few degrees lower than the ones registered farther inland during sunny weather. If we compare it (see the Ogimet chart below) with the values of my station in Karagiye, the average difference between the two is 4.4 degrees in favour of the depression. The biggest discrepancy (5.7 degrees) happened on 16th, while the smallest one (2.1 degrees) on 13th August.

This latter small difference was certainly caused by the easterly or south-easterly wind, which annihilated the sea breeze even near the coast, while on other days the city’s atmosphere was moderated by the cooler marine currents. As the low elevation of the depression gives an advantage of 1 degree against the level of Aktau, the measured 38.5 degrees would mean around 39.5 at -130 m, which is only one degree apart from the 40.6 degrees Celsius what I’ve recorded at my station.

Adding the 4.4 degree advantage to the average maximums of Aktau (see the Wikipedia chart) for the months of July and August will give 36.3, respectively 35.3 degrees Celsius average max for Karagiye, while adding the 2 degree difference (easterly dominance) to the 44 degree absolute maximum of the city will give around 46 degrees Celsius as a hypothetical heat record for the depression.

Addition: I’ve checked before the weather statistics of Aktau airport station on the Wunderground site’s history section (now unavailable) and saw that the maximums were 37, 37, 39 degrees Celsius (rounded values) for 11, 12, 13th August. As it is a little farther from the coast than the city, the somewhat higher peaks are understandable.

Comparison with Europe’s hottest areas

Regarding the extreme high temperatures, this summer was one of the most severe from the very start of the reliable meteorological measurements. The extensive heat domes affected the mediterranean area both in July and August during more successions, climbing the mercury of the thermometers to record or near record levels in many places. The most affected areas were the North African coast (Algeria, Tunisia), respectively Sardinia island and southern Spain where the temperature raised to 45-49 degrees Celsius.

This amount of heat is about 10-15 degrees above the average summer maximums of the mentioned areas, concretely at the level of Death Valley or of the Iran-Iraq-Kuweit triple border region, which are the hottest places of the Planet. Taking this into account it can’t be made a conclusive comparison between my study area and Southern Europe in the actual situation. Regarding the broader summer max averages Karagiye is probably alike the hottest areas of Andalusia (thus of entire Europe), which is around 35-37 degrees in July and August, while the absolute record potential could be between 46-48 degrees Celsius, also similar.

Altogether, for a “substitute plan” the research went quite well, both the conditions and the results can be considered decent for the context.

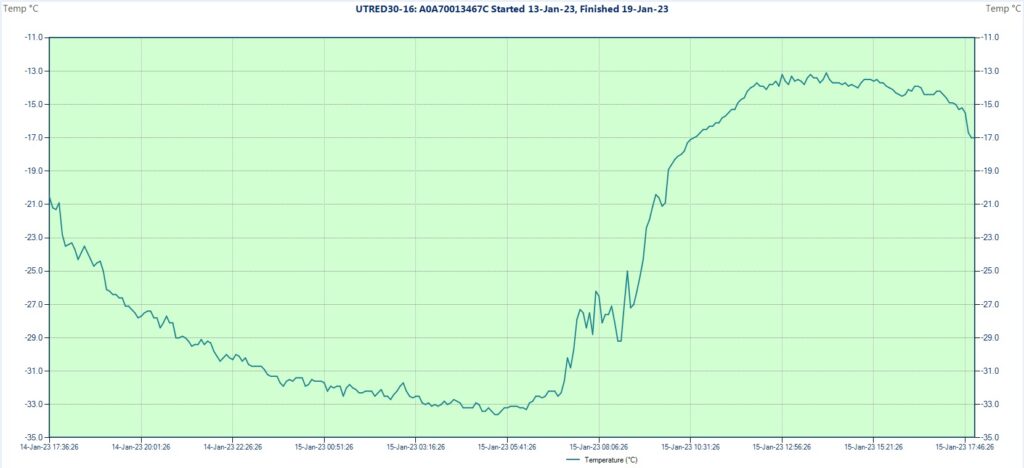

Interpretation of the logger’s graph (using LogTag Analyzer 3 software)

First night (14th January)

I installed the measuring equipment on the bottom of the closed basin in the second part of the night during clear and calm conditions. The logger set for 5 minutes intervals was started at 2:26 AM and the first reading showed -32.5 degrees Celsius. The second value is -33.2 C, which remains constant for the next 20 minutes, so its possible that the debut temperature actually was the same. I left the tripod around 2:40 AM and returned there in the early morning. During my walk from the tent situated aproximatively 2.5 km to the south I measured in the col between -26, -27 degrees with the handheld device, noticing also some wind there. The night remained entirely clear and on the bottom were the same calm conditions as at the time of the installation.

However, the temperature wasn’t lower in the dawn than before, the device showing -32.5 degrees at the first check. The recorded minimum was -34.1 degrees Celsius, which happened at 5:31 and 5:36 AM. A pretty constant night curve. But there are two more interesting aspects, one is the weak thermal inversion related to the context, which is around 6, maybe 7 degrees compared with the col, the other the complete lack of hoarfrost, which denote an extremely low humidity. I left the basin after sunrise. The entire day remained cloudless with only weak wind even on the ridges. The maximum, which I saw after returning in the next morning reached -16.3 degrees Celsius at 2:56 PM. That means a pretty big amplitude (17.8 degrees), which was expectable for a high altitude basin.

Second night (14-15th January)

The dark hours were completely starry again, but the wind intensified in the latter part of the night. Before the instability I measured down to -27 degrees inside my tent, expecting to see an even colder recorded minimum in the endorheic basin. It wasn’t the case, the lowest achieved temperature being only -33.6 degrees Celsius (at 5:21 and 5:26 AM), half degree warmer than before. As these two nights represents characteristic anticyclonic conditions I think that a generalization regarding the relatively weak thermal inversion of this place in snow-free context is very plausible.

While there before sunrise I observed the first cirrus clouds coming from the west. I left the basin soon and around noon also my camp. The day was generally fine but ocasionally windier, the sky partially covered by cirrus and cirrostratus clouds, with some thickening in the late afternoon period. I was spending my time around 10 km to the south of the research area staying in yurt with locals. The maximum of this day reached -13.1 C at 2:06 PM, which combined with the minimum of the dawn gives an amplitude of 20.5 degrees.

Third night (15-16th January)

From now on I will not visit the studied spot until the final day when I will collect the equipment, but will remain in its neighborhood (no more than 15 km away) most of the time. In the morning I measured -20.7 degrees with the handheld device at the yurt. The sky was mostly cloudy, overcast or variable with intensifying wind in the early afternoon when there were some very weak snow showers here and there, covering some parts with a new veil with a thickness of a few millimeters. In the latter part of the day the sky cleared up.

The diagram confirms the unstable weathern pattern, the curve being less regular and showing a smaller amplitude. The minimum reached -25.6 degrees Celsius at 9:25 AM, while the maximum -18.2 at 1:36 PM, the latter actually being colder than the late evening hours of the previous day. The 7.4 degree amplitude is the weakest one in the entire research period.

Fourth night (16-17th January)

While fair in the first part, the sky became overcast during the night. The curve reflects this as the minimum of -31.5 degrees Celsius was reached already in the late evening at 11:16 PM. In the morning I measured -20.8 degrees at the yurt, while observing a cloudy sky. The mostly overcast conditions persisted throughout the day in the whole area, including Ulaantolgoy where we made a trip with the car. Generally it was moderately windy.

The maximum reached -10.9 degrees Celsius at 1:56 PM, which is the highest temperature of the entire research. The daily amplitude of 20.6 degrees is also the biggest one, slightly exceeding the one from 15th. However, this can’t be considered a real endogen thermal span like the ones forming during stable weather conditions.

Fifth night (17-18th January)

This night was the windiest, more precisely the second part when I observed the yurt’s rooftop shaking a little at a certain time. In the morning the sky was clear, but because of the instability the temperature was even less cold than in the previous two cloudy days: -19.4 degrees. The minimum was reached again in the first part of the dark hours: -27.5 degrees Celsius at 11:21 PM when the conditions were more stable, while afterwards the temperature rised 10 full degrees during the second part of the night when the wind became dominant.

The maximum happened at 2:16 PM when the temperature climbed to -12.2 degrees, the second highest peak of the research. Today the sky was strikingly bright, even more transparent than on 14th, with only a few isolated clouds lingering above the higher peaks on the distance. It remained moderately windy throughout the day. The 15.3 degree amplitude can be considered average.

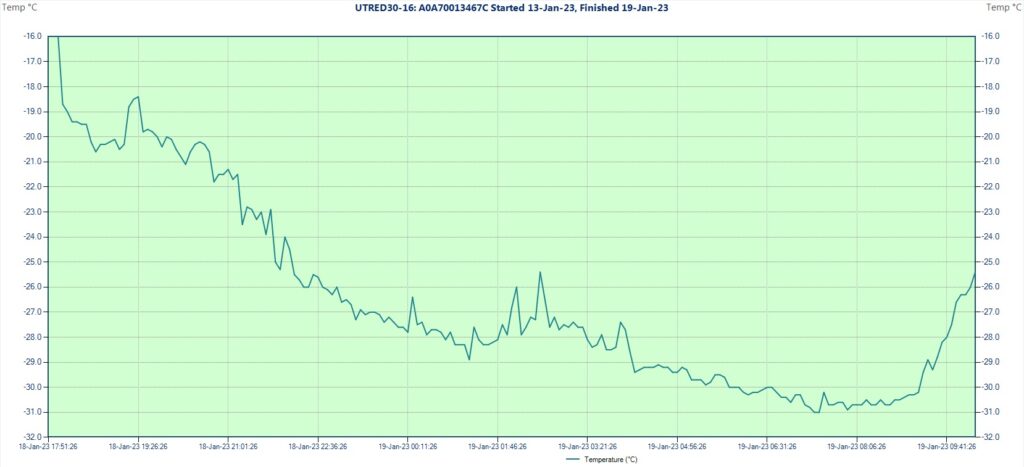

Sixth (last) night (18-19th January)

This was the coldest night by far at the yurt. The sky remained starry and there was nothing more than light wind. In the morning I measured -26.8 degrees. This time I observed also hoarfrost on the surface, thus the humidity was higher than before. I expected again to found a lower temperature in the closed basin (at least -33 to be precise), but surprisingly the minimum didn’t went below -31 degrees Celsius there, reinforcing my previous conclusion regarding the weak thermal inversion of this high elevation + snow-free combination.

The low temp was reached at 7:21 and 7:26 AM in the morning after a relatively regular night curve with some mild to moderate disturbance between 1 AM and 4 AM. Leaving the yurt, as we started our way back to Khovd, I went to collect the measuring equipment. The logger was stopped at 10:18 AM, the last reading showing -25.4 degrees Celsius. During this period it was calm and the sky was partially covered with cirrus and cirrostratus clouds.

The mean temperature of the 6 nights/ 5 days research period is -22.5 degrees Celsius, with the average minimum -30.6, respectively the maximum -14.1 degrees. The average daily amplitude is 16.3 degrees.

General conclusions

Comparing my logger’s results with the minimums registered at the official local stations situated also in generally snowfree areas

During my staying I visited the weather stations of Möst, Mönkhkhairkhan and Khovd where I asked about the parameters observed in these colder winter days. On 14th Khovd (Khovd aimag/ 1406 m) and Ömnögobi (Uvs aimag/ 1590 m) both recorded -28.7 C, the latter -31.2 C the day before, while Nogoonnuur (Bayan Ölgiy aimag/ 1480 m) -26.2 C, respectively -30.8 C on 13th. Möst (Khovd aimag/ 2020 m) reached -30.1 C on 14th and was slightly warmer both on 13th and 15th, while Mönkhkhairkhan (Khovd aimag/ 2090 m) was colder on 13th with -30.3, while having only -28 on 14th.

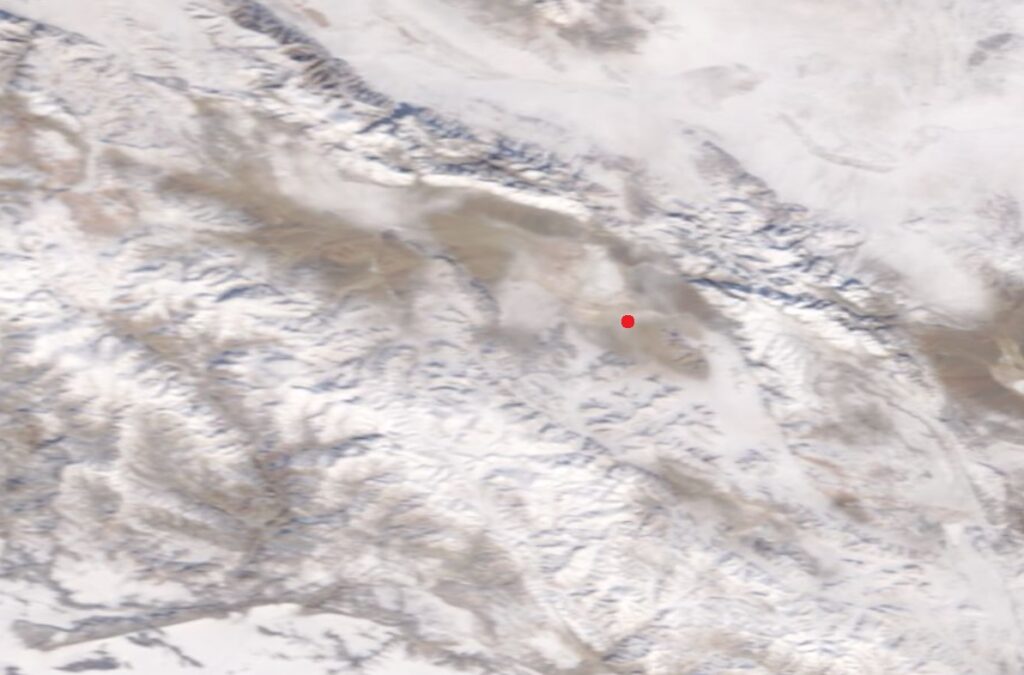

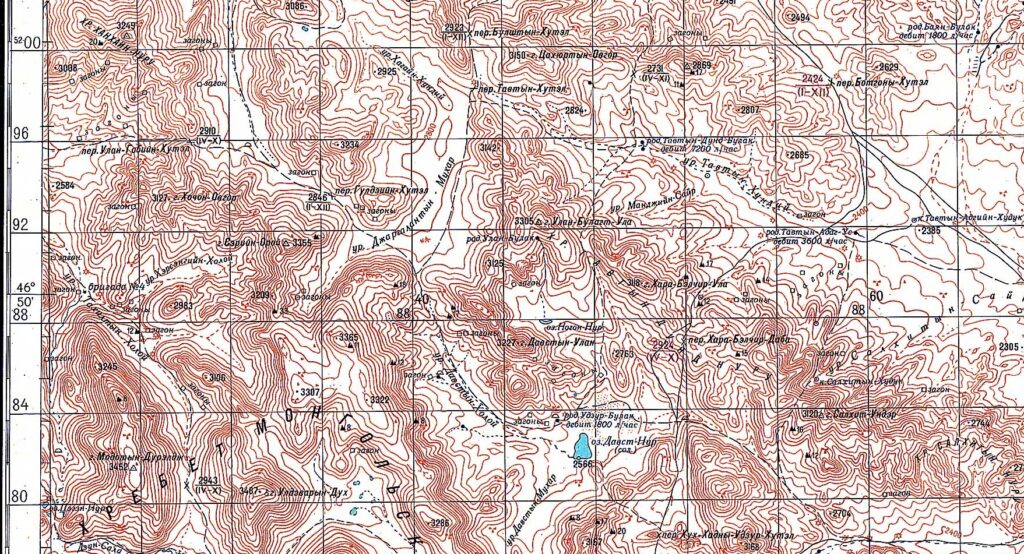

The coldest station which reported no snow cover at that time was Tsetsegnuur (Khovd aimag/ 1715 m) situated in a closed intermountain basin near the lake with the same name: -34.4 degrees Celsius on 14th January. This is even slightly colder than the value registered by my station. However, I checked the satellite image of the Tsetseg basin for that day (lower-right corner of the above image) and saw that actually there is a thin layer of snow in most parts. This doesn’t mean they gave incorrect data as the stations are obliged to report the snow depth they see at the rulers placed on the weather platform. The snow often can disappear sooner there, while in the surroundings still remains some.

At the weather center in Ulaanbaatar I asked if they have some statistics regarding the lowest temperature measured in snow-free conditions. They didn’t have, but together we searched for Tsetseg specifically and found a minimum of -36 degrees on 23th January 2012. At home I checked the satellite image also for this day and the result was similar: the basin wasn’t completely bare (see the picture below).

As a conclusion I would say that between the official weather stations of Mongolia indeed Tsetsegnuur has the biggest chances to reach the lowest temperatures. This because of the combination between the good topography (high+closed), respectively the rain shadow effect caused by the Mongol Altai’s main ridge which blocks the humid airmasses on the other side. The same as in the case of Jargalantyn Mukhar.

Final question: How cold can get in snow-free context and exactly where in the world are the best chances for this to happen? My opinion is that some areas of Mongolia and the northern part of the Tibetan Plateau could reach even slightly lower than -40 degrees in the best circumstances. As I am determined to research this little studied domain farther, the future certainly still has many other thrillful things to offer.

Journey photo album

To be continued…

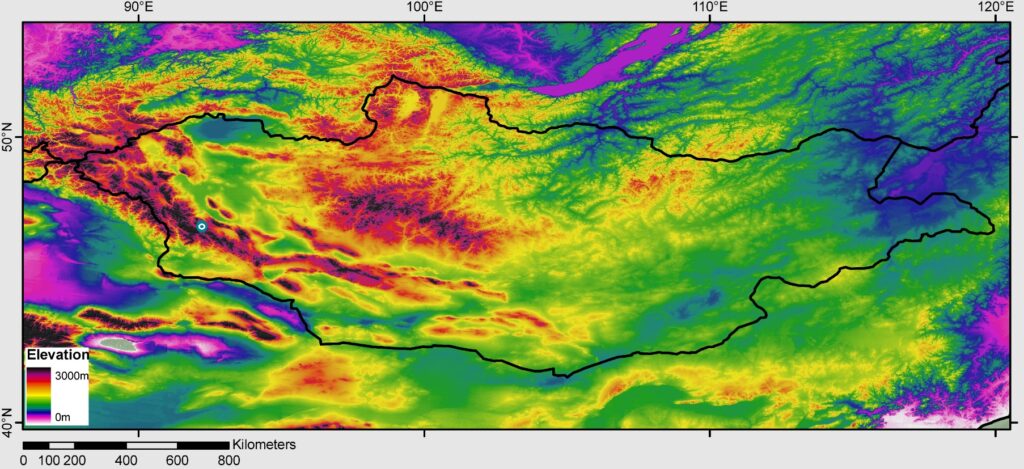

Choosing the target

Regarding my research plans, overall the best fitting country is definitely Mongolia, so it’s not a coincidence that I chose it again. It’s the perfect amalgam between an excellent natural context and decent travel conditions, even more now, when some other countries, which are on my bucket list from a long time are going through turbulent times.

The strong Central Asian anticyclone is the solid base for the severe cold in this part of the globe, north-western Mongolia being the actual center of this major baric system, bringing stable weather with clear skies, which favorizes the nocturnal cooling and the formation of thermal inversions in the valleys and basins.

From a long time I have a dominant wish regarding the extreme climates. It’s the particular case, when there is no snow on the ground, but it’s still unusually cold. I would even say that this is my favorite research context between all the existing combination possibilities. It’s the certain kind of “otherworldliness”, reminiscent of Mars or Moon, which gives it the special charm.

For many years I followed and remotely monitored the weather’s evolution in the spots with the best potential, waiting for the ideal congruence to occur. However, as a generality covering many aspects of life, the best things usually doesn’t happen easily. Even if you are ready to pay the price. But this is the “entry level” without any doubt. So here I am now targeting the fragile equilibrum between extreme cold and bare ground.

Some people could ask, why is this so difficult to achieve? Well, there are two major causes:

The first is based on simple physics, namely the fact that the snow cover seriously enhances the cooling of the air above, partly because of blocking most of the Earth’s internal heat under its isolating blanket (air particles between the snow flakes), then because its white color reflects the Sun’s heating rays during the daytime. In short: without snow cover can’t be that cold.

The second is related to the weather patterns, which have their own limitations regarding the relation between snow fall and snow melt/ sublimation in a certain situation. Thus, during very cold weather if a little bit of new snow falls (even less than 1 cm) it will last pretty long time on the frozen ground. All these together are severly narrowing the range of possibilities to found a proper context regarding this plan.

After a thorough analysis of concrete weather/ climate data, satellite images and topography I got to the conclusion that the best chances to produce very cold without snow on the ground are some areas of Western Mongolia, respectively the northern part of the Tibetan Plateau. These regions receive minimal precipitation during winter, while at the same time cooling down to almost arctic levels. Tibet has the altitude, Mongolia the latitude advantage.

How about to have both? Maybe a compromise between a relatively high elevation and a sufficiently nordic setting will be the best choice. Let’s check this out.

There are some parts in the arid interior side of the Mongolian Altai where the elevation is above 2500, even 3000 meters, while the latitude is between 46-47 degrees N. A closed basin here should be great for sure. I was very glad when realizing there are some promising topographical settings.

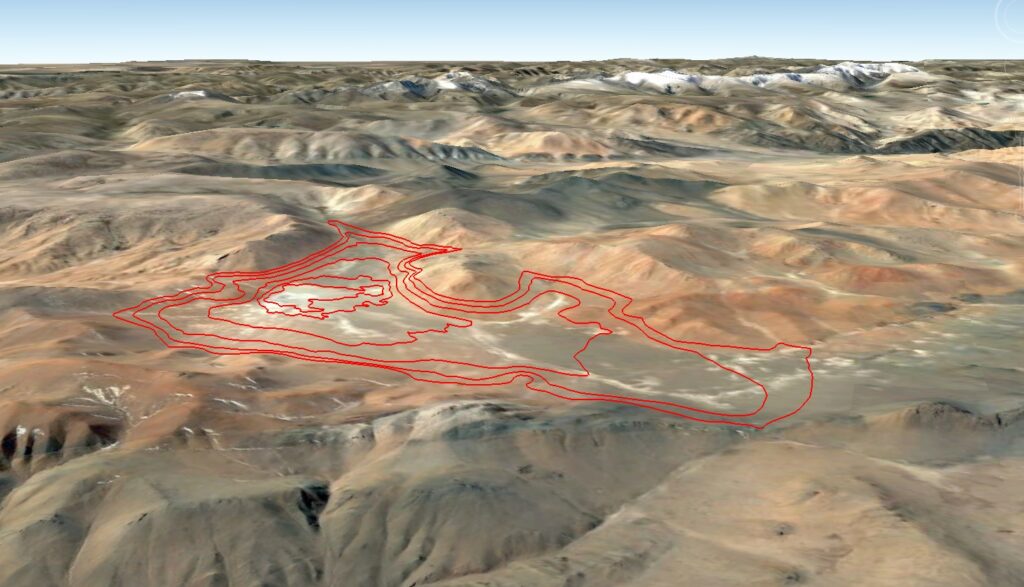

The best seems to be the one named Jargalantyn Mukhar, a 75-80 meters deep bowl situated on a semi-desertic plateau of rusty nuance in the central part of Khovd province. Its bottom is situated at 2780 m elevation and looks like it’s completely dried up (only solonchak, no lake). It’s the second highest between all the endorheic structures with significant depth in Mongolia, surpassed only by a smaller one with a quarter of its depth and also more exposed.

According to the statistics of the weather stations located on the mongolian side of the Altai range the average precipitation of the winter months is around or even less than 1 mm, Tonkhil receiving no more than 0.5 mm during each. I think it could be similar in my target area too. Certainly rain shadow, respectively föhn effect, the other side getting almost all the rain and snow.

After analyzing the seasonal satellite images of the last two decades which prove that in more winters the snow cover was completely missing there, I became optimistic that with some luck this particular place could deliver what I am searching for.

Brief summary of the research

Because in this plan the uncertainty factor was significant, I was prepared with a “Plan B” for backup, in case that the bare ground context could not be found in the targeted area. This is a little more complicated as it sounds, as the “Plan A” location is strictly reserved for snow-free conditions, thus in case of a new snowfall the study area will move to a different place. This is because the intermediate situation when there is only a thin snow-cover is not good for any kind of research, therefore I will rather go to an area which already had snow before to be able to reach lower temperatures.

Actually there were some chances to snow a little just before my plane will land in Mongolia, so I was very pleased when checking the newest satellite imagery while in transit in Istanbul saw that the snow-free condition persisted in the chosen basin.

My plane landed in Ulaanbaatar on 12th January in the morning. Because of the forthcoming anticyclone I was rushed to reach the target as soon as possible, thus didn’t spent the next night in Khovd, but headed in the evening directly towards the high plateau in Möst sum with the 4wd driver. Little sleep, even less acclimatization. The biggest part of the road is brand new chinese asphalt, only the latter 20 km’s or so is dirt track. At the start of the latter our host was waiting to guid us towards the target. Pushing the limits, after mounting the tent nearby, on 14th January in the night I managed to reach the bottom of Jargalantyn Mukhar basin.

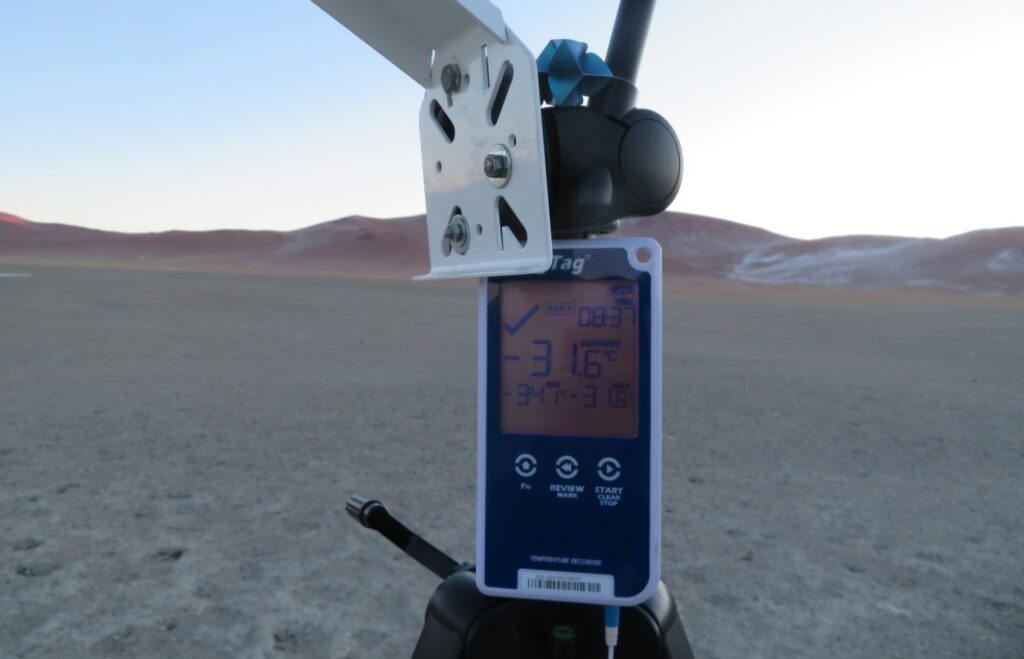

The exact coordinates are: 46.8586 N, 92.2189 E, the elevation 2780 m. The height of the sensor above the ground is around 170 cm. At 2:26 AM the mini weather station started its operation. The device is recording a temperature value every 5 minutes. First reading was -32.5 degrees Celsius, then, just before leaving I saw -33.2 C.

After the installation I went back to my tent and rested until the early morning, when returned to the tripod to check the night’s minimum. The lowest recorded value was -34.1 C while the actual temperature was slightly rising despite there were no clouds nor wind on the bottom.

In the nearby col, situated 80 meters higher I measured between -26, -27 degrees, accompanied by some breeze. It seems that the inversion is not so strong here, despite the very dry air, which holds back the hoarfrost to form even at below -30 degrees.

I spent the day and the next night too in the surroundings, sleeping in tent and returning again in the second morning to verify the instrument. The minimum wasn’t lower, but pretty close: -33.6, while the maximum reached -16.3 degrees Celsius. The sky was completely clear during this interval, but in the latter part of the second night the wind became more active.

After securing the tripod with some improvised weight (hanging rocks inside a bag) to can handle windier conditions too, I left the research area on 15th January around noon and except a short trip to Möst sum’s center, I spent the next four days just a few km’s away, sleeping in yurt with locals. During this interval the sky was variable (sometimes windy) with some very weak snow showers here and there on 16th.

I’ve done a few hikes to the nearby rocky peaks and visited Davst Nuur hypersaline lake, meanwhile observing the nomadic activity (sheeps, goats, horses, yaks) and wildlife (bearded vulture, ibex, hare). No wolves, but the locals said there are many on the other side of a range, coming over and attacking the livestock regularly.

While there, the studied basin itself looked empty, but I saw herds of animals and yurts not far from the salt marsh (2-3 km), also a few motorcycles passed by. All in all, despite the remoteness and harsh conditions there is some human activity in the whole area, the signs of grazing being often visible.

I returned to collect the equipment on 19th January in the late morning and found the installation in its place with the gadget intact and functional. All data was correctly recorded. The lowest temperature remained the one from 14th, while the maximum reached -10.9 on 17th January.

A productive research for sure.

The instruments used on the field

-One LogTag UTRED30-16 data logger with the measuring range between -40 and +99 degrees Celsius, an accuracy of 0.5 degrees Celsius and a resolution of 0.1 degrees Celsius.

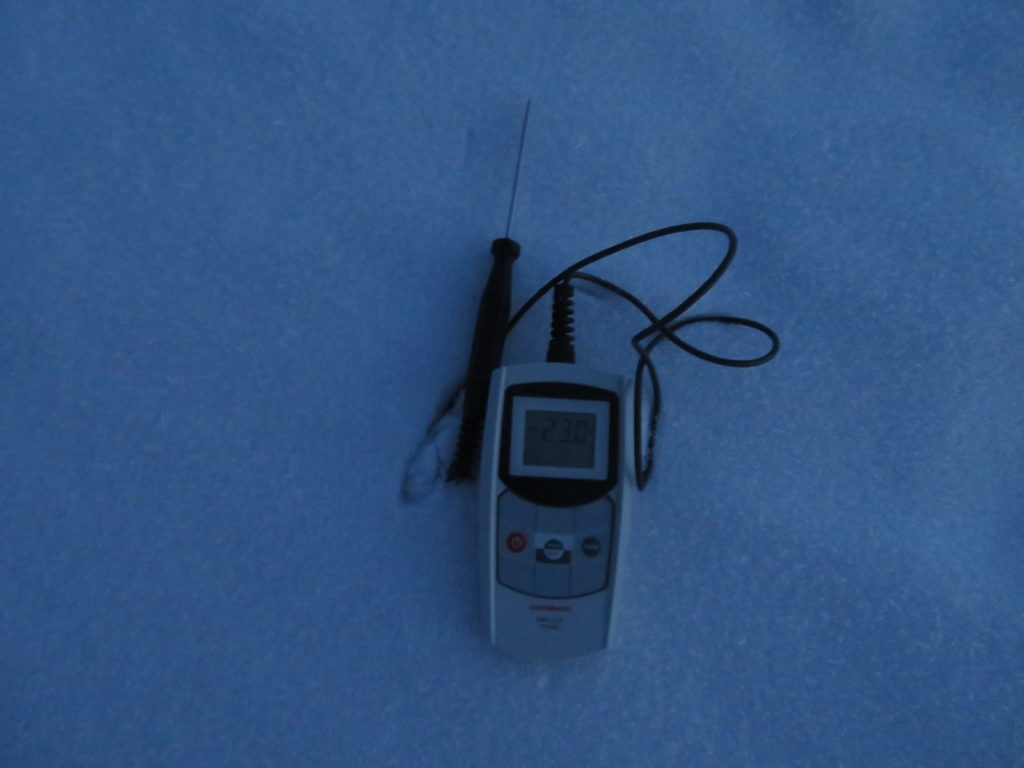

-One Greisinger GMH 2710-T digital precision thermometer with the measuring range between -199.9, +200 degrees Celsius, an accuracy of +-0.1 degrees Celsius and a resolution of 0.1 degrees Celsius.

-One photo camera tripod serving as the support for the instruments.

-One helical solar radiation shield from Barani Design Technologies: https://www.baranidesign.com/

To be continued…

Interpretation of the logger’s graph (using LogTag Analyzer 3 software)

First day (June 21st)

It is the single day when I’ve spent significant time nearby the measuring equipment in the wadi. It was haze during my hike through the salt flats of Lake Assal before entering the gorge, with little wind. The logger started to record at 10:43 AM and the first reading can be considered legit as I waited sufficient time with the sensor placed under the helical shield to accomodate the ambience before pushing the start button. As I set the device for 2 minutes logging (short intervals) the curve has the typical “saw aspect” with many small ups and downs inside the general “big waves”. The temperature was rising more abruptly until 2:17 PM when reached 47.0 C, after which slowly increased until 3:59 PM when recorded the day’s maximum temperature of 47.4 degrees Celsius (quite normal evolution). During this time the sky was clear or partially covered, but the north-western clouds never managed to block the sun.

I left the area after 5:18 PM, when the temperature was already descending and the sun was reached by the clouds just a little before disappearing behind the walls of the valley. After spending some time outside the gorge where encountering a sandstorm after 6 PM I later returned to the tripod to see if it survived the strong wind (luckily yes). This interval coincides with a more abrupt drop of 2.3 degrees between 6:09 and 6:25 PM (from 46.3 to 44.0 C), following a more constant period even if the sun was already gone for almost an hour.

After this the descend is more natural until 2:57 AM when it reached 39.4 C, the lowest temperature of the night. Before 5 AM it was a strange rise from the already very high base to 40.9 C, then started to drop again. The lowest reading of 38.1 C happened shortly before 8 AM in full daylight, but the sun probably reach inside the gorge only later. I’ve spent this night around the lake and measured similar temperatures with my handheld device (38-40 C between 0 – 6 AM). Meanwhile the sky became cloudier.

Second day (June 22nd)

I left the area during this morning and returned only in the last day (26th in the late afternoon) to collect the equipment. This second day is a weird one as it is composed of the lowest maximum (44.3 C at 3:15 PM) sandwiched between the two highest minimums (38.1 and 37.6 C).

This and the fact that it has some shorter abrupt drops in the early evening (again between 6 – 7 PM) suggests that it was windy, another sandstorm is very likely. However the mentioned max and the min were both registered in the expected period (afternoon, respectively early morning).

Third day (June 23rd)

During this day I was on a trip around the western part of the Ghoubbet bay, so not too far from Lake Assal (25 km from the gorge). The morning was cloudier, while the midday and early afternoon sunny and very hot. I measured 46 degrees on the black lava field with my handheld thermometer, while the wind was moderately blowing.

From the morning there was a constant rise until 3:03 PM when the day’s maximum of 47.2 C was registered and the same value was reached again at 4:25 PM after a small setback. This second peak was instantly followed by a big drop of more than 3 degrees in 6 minutes, then the curve became more normal. This coincides with the time when I was finishing my hike and saw some bigger clouds forming in the north-west. Probably it was again only wind, without rain. We can also observe on this day an unnatural 3 degree warming in the evening between 9 – 10 PM (exceeding 40 degrees again), certainly khamsin. The descend happened only after midnight, while the minimum was 35.2 C in the early morning.

Fourth day (June 24th)

This day the temperature has a quite normal evolution, reaching 44.6 C at 3:07 PM following a constant rise, while after 4 PM starts the descend, which has no abrupt changes (except a slight rise in the evening) until 5:05 AM, when recording the minimum of 33.3 C. This will be also the lowest temperature of the entire measuring period.

I was in Djibouti city on this day, so I don’t have direct info about the cloud cover over the area.

Fifth day (June 25th)

On this day I was again on a trip to Ghoubbet bay, this time in the south-eastern part, thus a little farther from my study area (around 45 km). It was less haze than on the other days, from the high ledge of the plateau I could see the other side of the bay (though only barely).

This day the max was reached a little earlier than usually: 44.5 C at 2:29 PM, with a slight setback (almost constancy) afterwards, the concrete drop starting only after 5 PM with some abrupt changes in the first half hour. It was again a +2 degree rise in the evening, followed by a less constant decrease until dawn, when the minimum of 35.8 C happened.

Sixth, last day (June 26th)

Today in the late afternoon I came back to Lake Assal to collect the equipment. It was haze again with a few clouds in the sky (not clearly seen). The timing was good as I reached the gorge only after 6 PM when the temperature was already decreasing, thus having the daily maximum recorded also for this day.

The peak of 46.1 C was reached at 3:59 PM, exactly in the same minute when the first day’s 47.4 C happened. We can observe on the graph an abrupt early morning rise of 1.6 degrees, respectively a +2 degree unnatural drop after 1 PM. The rest is more or less a constant rise until 4 PM, then decreasing. The last reading was 43.6 C at 6:07 PM when the logger was stopped.

The mean temperature of the 6 days/ 5 nights measuring period in the wadi is a round 40.0 degrees Celsius, an unusually high average for sure. The mean maximum was 45.7 degrees, while the mean minimum, 36.0 degrees. The maximum is similar to the ones measured at the hottest weather stations in the world: Death Valley (Furnace Creek), Persian Gulf states (Ahvaz, Basrah, Jahra), central-western Sahara (In Salah, Reggane), Pakistan (Sibi, Jacobabad) and the Ethiopian Danakil (Dallol). The minimums seems to be higher than anywhere else on the planet, no station recording above 35 C average lows in any month.

General conclusions

Comparison with Djibouti (Ambouli International Airport) weather station

According to Wunderground’s history, but also mentioned by my driver Houmed, the temperature in Djibouti city reached 45 degrees Celsius on 21st June (2-3 PM), when the 47.4 C peak was recorded in the gorge near Lake Assal. This is only one degree shy of the city’s absolute record and certainly was caused by the khamsin. As Ambouli’s available values are all rounded I must work with these: in 21st the difference is 2.4 degrees in favour of Lake Assal.

Also 22nd was a very hot day in the capital, when 44 C was measured in the same early afternoon interval. As I spent this day in the city, I can confirm from personal experience that the heat was extreme indeed. More than that, this day the two peaks were very similar, my logger measuring its lowest maximum in the gorge: 44.3 C

On 23rd the difference is bigger, the city recording 42 degrees, while Lake Assal 47.2 C: 5.2 degrees. June 24th was the “mildest” day in the capital with only 37 degrees (but likely with high humidity), while my station recorded 44.6 C: 7.6 degrees difference, the biggest one. On 25th the discrepancy is smaller again, Djibouti reaching 41, while Lake Assal 44.5 C: 3.5 degrees. In the last day, on 26th, the disparity is again high: 39 vs 46.1 C: 7.1 degrees.

The average difference between the maximums for the six days is 4.3 degrees in favor of Lake Assal. Due to the coastal placement Djibouti is usually more humid with a high heat index even with only 35-36 degrees Celsius, while Lake Assal is much more affected by the dry wind.

Comparison with Dallol (Ethiopian Danakil)

As Dallol weather station operated only between 1960-1966 and the datas are also kind of questionable, this comparison will be less concludent.

If we take into consideration the month of June, Dallol’s mean maximum is one degree higher than the average max of my six day research near Lake Assal: 45.7 degrees. However, I have some doubts regarding Dallol’s value, which compared to its absolute June max looks unusually high: only 1-1.5 degrees difference between them. That’s just too small even for 6-7 years of measurement. As I saw a lot of suspicious climate charts and tables in my life with significant differences even between the same locations, my general opinion is that many of them is based on algorythms and are not coming from real, ground based measurements.

Final question: Could Lake Assal’s depression beat the actual World Record for the highest temperature? We could not exclude this, but my opinion is that the upper limit must be somewhere between 50-52 degrees Celsius here. I think there are more chances to beat the highest low temperature for one night, the actual record being 44.2 degrees Celsius in Khasab (Oman).

I consider this research a successful one, actually it’s the first one flawlessly completed with all days and nights correctly monitored.

Journey photo album

To be continued…

Intro: the warmest capital city

Together with Khartoum in Sudan, Djibouti city is the hottest capital in the world, having a yearly average temperature just a little shy of 30 degrees Celsius. While the “winters” are warm (kind of an european summer), the hot season is sweltering and the high humidity, characteristic for the coastal areas make the tropical ambience even more oppressive. The heat doesn’t go away even in the night, thus the living is very challenging without air conditioning, especially for non-natives. In the dark it almost feels unreal, like you are trapped inside a giant sauna without walls.

The city has a population of around 600.000, represented mostly by issa (somali) and afar ethnic groups with some arabs, french and other minorities beside. The former french colony is a busy strategic port close to the Red Sea’s Bab-el-Mandeb strait and more countries have military bases here. Before known as “French Somaliland”, after gaining the independence in 1977 the small country received the same name as its capital. Unknown for many travelers, the tourism is not very well developed here, but is rising in the recent years. Security is taken seriously, police presence is common. Djibouti’s downtown is quite noisy, with many honking green/ white taxis and old minibuses looking for the next passenger. Ambouli International Airport is close to the city and greeted me before midnight on June 18th with the first dose of african heat.

Choosing the target

The most iconic place associated with heat in the meteorological sense is undoubtedly the Sahara desert. An endless, empty place with the size of a continent presenting huge, sunbaked sand dunes and barren, rocky terrain. Temperatures are known to be very high there, often exceeding 50 degrees in the shade. Wait. Is this really true? Well, partially. Actually there were only a few cases when reliable temperatures above 50 degrees were measured here, the 51.3 degrees Celsius recorded in Ouargla (Algeria) on 6 July 2018 being the most certain one. Some old readings like the famous 58 degrees from El Aziziya were infirmed in the later years after specialistic investigation of the used equipment and measuring conditions. Long story short: naturally occuring +50 C air temperature is less common than people think.

Regarding my personal research, from the three main extreme categories (Cold, Heat, Amplitude) heat was the last to come. Actually it’s not exactly the first time, a few years ago I’ve visited the Ethiopian side of the Danakil depression with the same purpose, but the research was unsuccesful as I couldn’t collect the equipment from an inactive volcanic crater because of … let’s say “bad luck”, having to deal with unreliable local collaborators. Thus it’s understandable that I felt a strong need to come back to the Danakil and “finish the job”.

The sunken desertic area of tectonic origin is situated on the territory of three countries: Ethiopia, Eritrea and Djibouti. While the first one has the biggest portion, Djibouti owns the lowest spot, represented by the shores of Lac Assal at 155 meters below the sea level, also the deepest land in Africa and second in the world after the Dead Sea’s depression*.

While second to the Dead Sea regarding the elevation, the raport between the two is reversed when we are talking about the salt concentration, Lake Assal being the saltiest lake of considerable size in the world (ten times more than the ocean), surpassed only by two small ponds (one in Antarctica, the other also in the Danakil), so one can easily float on the surface without sinking.

I have an old passion for below sea level places, which usually have a very hot climate (Death Valley in the USA is the best example). Why? There are two main reasons for this: first because of the general rule that normally temperature drops with elevation (6.4 degrees by 1 km), secondly because these places are parts of very dry, desertic environments, strong evaporation being a basic condition for their formation. A consequence of the latter is that they are often associated with salt marshes, the residue of the former lake. Badwater in Death Valley (-86 m), the southern part of the Dead Sea (around -400 m), Aydingkol in the Turpan Basin (-154 m) and Lake Assal (-155 m) all have these same two things in common: salt flats and extreme summer heat.

Dallol in the Ethiopian Danakil is considered to be the place with the highest average temperature in the world with a whopping 34.6 degrees Celsius, according to the short period of measurements from 1960 to 1966. June is the hottest month with a mean maximum of above 46 degrees, very similar to the well known “heavyweights” of the domain like Death Valley, the Kuwait-Iraq-Iran border area near the Persian Gulf (July-August) or the Jacobabad-Sibi plain in Pakistan (May-June). However, unlike the former mentioned ones which all reached 52-54 degrees at a certain time, no temperatures above 50 were ever recorded in Dallol, 48.9 C being the highest measurement. An unusually small gap of less then 3 degrees between the typical and the extreme values for sure, even for only 6-7 years of data. The heat is “at home” here, it’s never coming from somewhere else as in the case of most places (like Saharan origin heat in Europe for example), this must be the main reason for this constancy.

While before I’ve chosen the more interior part of the Danakil (Afdera Lake area) to completely avoid the moderating effect of the sea, now I knew that Djibouti’s Lac Assal is definitely not “too close” to the coast as in the summer months the wind (known as Khamsin) is blowing from the land, heating and drying everything on its way. The difference between the two regions is in the cooler part of the year when the wind is coming from the east (Indian Ocean), internal areas remaining warmer than coastal ones. Lake Assal’s southern shore is situated only 10 km away from the Ghoubbet-el-Kharab bay, an almost completely closed part at the very end of the Gulf of Aden. Actually the highly saline lake gets its water from this bay through the tectonic fissures.

The general area was defined, let’s look at the small scale features. Basically I want to set the equipment at a little distance from the lake (respectively the salt pan) to have such ground below, which can heat up more (sand or gravel). Beside this I try to identify some topographical enhancement, without loosing too much elevation. After looking thoroughly everything around on GoogleEarth I found the right spot inside a gorge, just a few hundreds of meters from the salt flats. The dried riverbed’s name (known as “wadi” or “oued” in the arab world) is Kadda Galeita. Regarding the elevation the satellite data is not so precise here because of the small sizes, thus I partially concluded from the visual aspects that this place must be the best one for my purpose. Beside the general “canyon effect” (part of the solar radiation is reflected back by the walls), the concave curvature of the gorge is looking exactly to the NW, from where the strong sun will strike the slope in the early afternoon hours. Despite being on the Northern Hemisphere, because it’s inside the tropics, in this period of the year the sun passes slightly to the north above the land and June 21st is when the northern deflexion is the biggest.

In Djibouti the meteorological measurements are scarce. It seams that outside the capital’s airport there are no other weather stations at all, anything else is based on hypothetical approximations (both the regional forecasts and the climate diagrams). The city’s highest recorded temperature is 46 degrees Celsius (June and July), also just a few degrees above the summer months average maximums (40-42 degrees), a characteristic of the lower latitudes.

At present industrial scale salt extraction is happening at Lake Assal, consequently in the recent years can be reached on paved road. However the area is still kind of remote as there is no public transport from the Tadjoura main road, usually only expensive private tours and taxis are taking the tourists there. My target is about 10 km far from the “parking lot” (the end of the asphalt road).

*The Sea of Galilee (-212 m) often mentioned as the second lowest basin in the world actually is a part of the bigger Dead Sea depression. They are linked by the Jordan river, so can’t be considered a separate basin. However it is the second lowest lake.

Brief summary of the research

I arrived in Djibouti on June 18th in the late evening and after two days of rest and some acclimatization in the muggy heat of the capital, in the early morning of June 21st I was heading with a private driver to Lake Assal, which lies about 110 km west from the city.

After leaving the main Ethiopian road with heavy truck traffic, we continued on the Tadjoura way around the gulf of Ghoubbet, then turned left and reached the end of the asphalt road on the lake’s southern shore after 8 AM. From here I started the hike on the salt pan towards the target situated inside the gorge.

The weather was already hot and became oppressive while reaching the exact location in the wadi after 10 AM. There were only a few clouds, but the characteristic summer haze caused by the hot and dry khamsin wind was present. However, I felt only weak air movement until now.

The bubble-aluminium foil protected data logger (I positioned the device’s screen to face south) and the Barani solar radiation shield under which its sensor was sheltered were mounted on a tripod whose legs were farther stabilized with nearby rocks.

The exact coordinates are: 11.686346 N, 42.341225 E, the elevation around -130 meters. The height of the sensor from the ground is 160-170 cm. At 10:43 AM the mini weather station started its operation. First reading: 42.4 degrees Celsius.

I waited in the shade nearby the research equipment until late afternoon, meanwhile checking the temperature more times and measuring also the ground in the early afternoon. With some luck I caught the highest air temperature live: 47.4 degrees Celsius around 4 PM and saw 73.9 C on sandy surface around 1 PM. The sky was partially covered in the hottest period, but the clouds coming from the NW never managed to block the sun.

After a sandstorm, which hit my camp in the early evening, I’ve spent the following night outside, hiking back to the asphalt road until the morning were my driver picked me up. The evening and night was still extremely hot, this phenomenon felt even more outlandish than the peak heat of the day.

I couldn’t sleep or even rest until dawn as the temperature never dropped below the human body’s and the hot wind was making the real feel even worse. Meanwile the sky became cloudier. This night’s minimum temperature in the gorge was 39.4 C !

I’ve spent the next days sleeping in the city with two separate trips to the Ghoubbet-el-Kharab bay using public transport: one to the volcanic area with new lava fields on the western side of the gulf and one to the higher plateau on the south-eastern part. Because of the proximity to the ocean, the capital is much more humid than the internal areas, having the heat index higher for the same temperatures. Here you are constantly sweaty, while at Lake Assal the khamsin sucks out all moisture from you.

I returned to collect the equipment on 26th in the late afternoon (haze again) and found the tripod standing in its place on the wadi’s floor with the logger functional and everything intact. The research was successful, all data was correctly recorded. The first day’s 47.4 degrees wasn’t surpassed on any other day, but was approached on 23rd with 47.2 degrees. The lowest daily maximum was 44.3 on 22nd, while the minimum of the entire measuring period 33.3 degrees Celsius in the morning of 25th.

During my staying in the Lake Assal area I didn’t encountered any wild animals outside of four camels and hearing some high pitched bird noises inside the gorge. The vegetation is completely missing on the salt flats and is also very scarce on the sandy-gravel surface. No acacia trees, only some small tufts. At the end of the asphalt road live some locals (mostly youngsters) who sell salt and other mineral related souvenirs and there is some activity at a chinese salt extraction plant. No other tourists were present as it is low season because of the heat.

The instruments used on the field

-One LogTag UTRED30-16 data logger with the measuring range between -40 and +99 degrees Celsius, an accuracy of 0.5 degrees Celsius and a resolution of 0.1 degrees Celsius.

-One Greisinger GMH 2710-T digital precision thermometer with the measuring range between -199.9, +200 degrees Celsius, an accuracy of +-0.1 degrees Celsius and a resolution of 0.1 degrees Celsius.

-One photo camera tripod serving as the support for the instruments.

-One helical solar radiation shield from Barani Design Technologies: https://www.baranidesign.com/

To be continued…

To be continued…

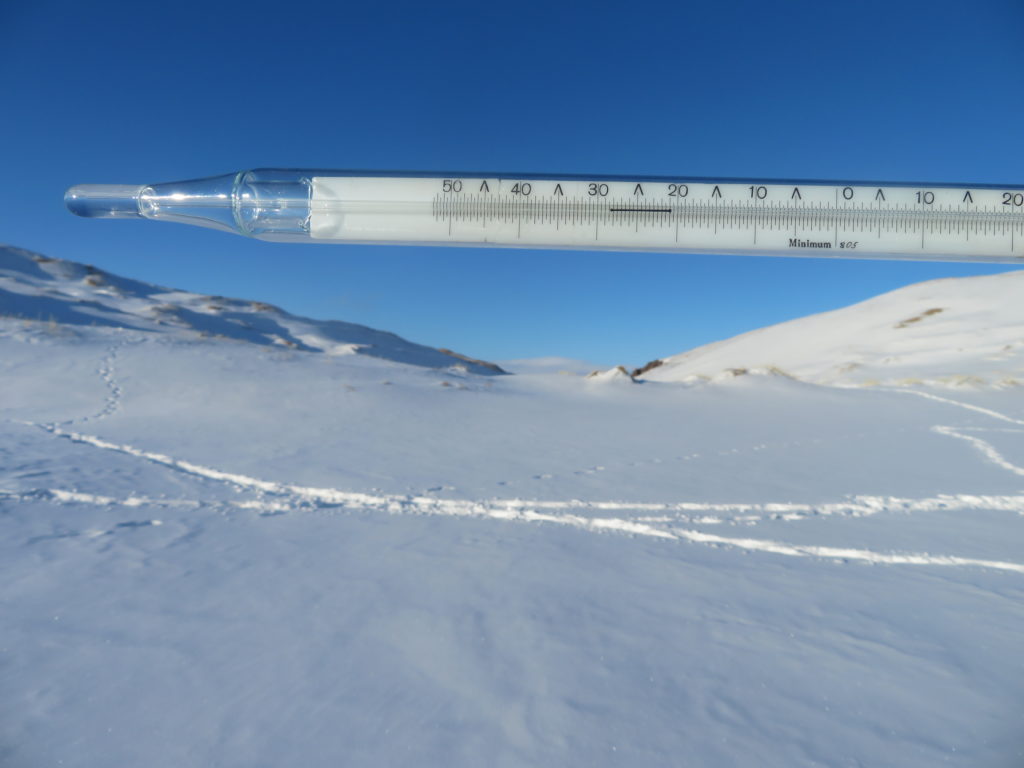

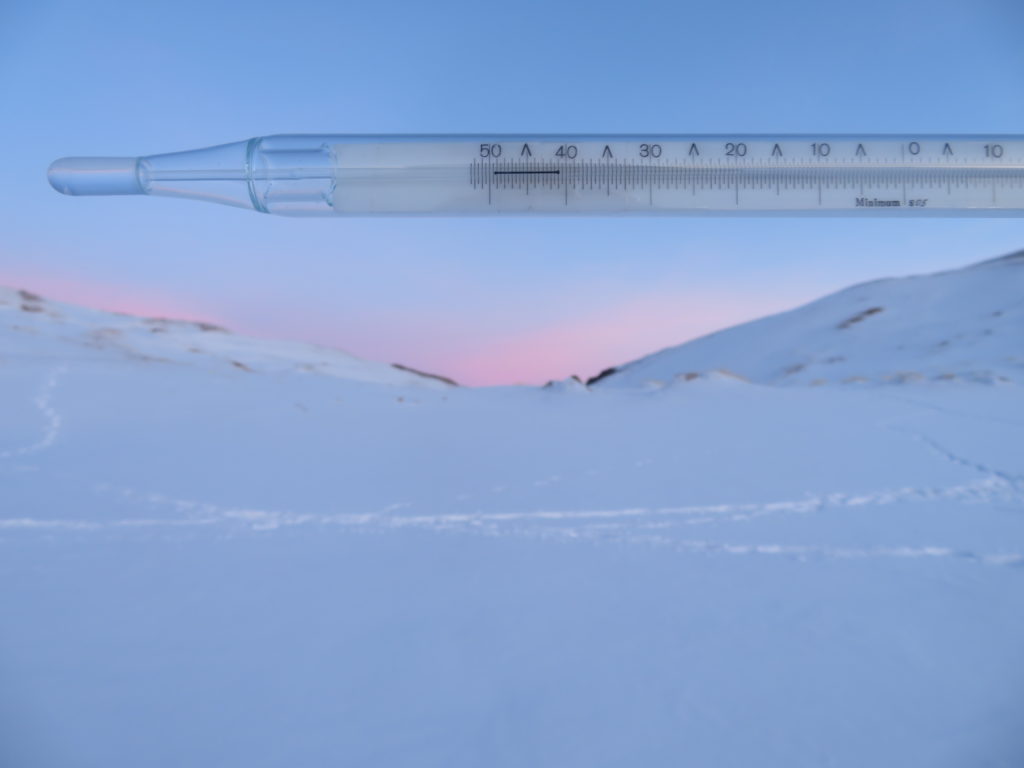

First research night (12-13 January)

The tripod with the minimum thermometer was set around 5 PM at the bottom of the basin. The sky was clear, no air movement, still sunshine at that time. The alcohol column of the instrument showed -28 degrees Celsius. Shortly after the installation became shadowed and until 17:40 (when I left the hollow) the temperature decreased to -33.5 degrees. Near the snow surface I measured -36 degrees.

The first part of the night was completely clear and calm at my tent. After 3 AM (it was almost full moon) I observed some cirrus, than cirrostratus clouds invading the sky. At dawn I measured -17 degrees at head level and -23 close to the surface near my tent. In the hollow was -35 degrees in the early morning (-37 close to the surface), while the minimum of the night reached -41.9 degrees Celsius. This will remain the lowest temperature captured in the entire research period. In the same night Tsetsen Uul (the most representative weather station of the area) reached -38.4 degrees.

The 13-17 January interval

I left the research area in the morning of 13th January. As I had no logger to record the temperature curve, the single certain data what I will have after my return is the minimum value for the entire missing period. I visited the hollow for the second time in the afternoon of 17th January, when I found the index of the instrument stopped at -38.5 degrees Celsius. I can’t be sure which night gave this value, can’t even exclude the same morning when I left the basin. However most likely happened on the night from 14 to 15 January, when Tsetsen Uul reached -37.2 degrees.

Second research night (17-18 January)

The afternoon was changing from full sunshine to partly cloudy (cirrus-cirrostratus with some altocumulus lenticularis) and was warmer than on 12th, with the temperature around -21 degrees. The evening started well with clear sky and still air, but later in the night it became windy. No clouds till the morning, but the intensified wind completely destroyed the inversion of the basin. The temperature raised from the -40.9 minimum value to above -20 degrees before the sunrise. The same pattern can be observed in the statistics of Tsetsen Uul, which recorded -36 somewhere in the early night hours and warmed up to -19 degrees till the morning.

The 18-22 January interval

I left the research area in the morning of 18th and visited the hollow again in the afternoon of 22th January, when I found the thermometer’s index stopped at -39.6 degrees Celsius. This almost certainly happened in the morning of 19th January, when Tsetsen Uul recorded -35.6 degrees.

Third (last) research night (22-23 January)

The entire day was generally fine, also much warmer, with the afternoon temperature of -16 degrees. There were only intermittent light air movements, but thinner cirrus and cirrostratus clouds were partially covering the sky constantly. This setting continued also in the night, when the sky was starry, but slightly blurred. No wind till the morning. I’ve measured -17 degrees near my tent at dawn, which was a surprisingly high value, as I saw 2 degrees colder in the early evening hours in the same place (!) In the basin the minimum thermometer’s index was stopped at -36.8 degrees, while the temperature at the moment was also close to this value (around -36 degrees). This was a good night, very likely presented the characteristic temperature curve, but because of the too high starting temperature couldn’t reach too low, despite the 20 degrees of decrease.

But the most impressive happening was when I descended in a hollow between the dunes, just beside my tent. Certainly no more than 10 meters deep and with the drainage area not bigger than a soccer field. To my great surprise at the bottom of this banal concavity the head level temperature was -37 degrees Celsius at 8 AM (already -35 in the earlier part of the night), a full 20 degrees lower than on the nearby ridge and even slightly colder than the minimum for the entire night in the big basin with hundreds of times more drainage area! Meanwhile the near surface temperature was -39 degrees.

Compared with Tsetsen Uul the Burgastyn Els station reached lower minimums in all the 5 described intervals. The smallest difference is 1.1 degrees, the biggest 4.9 degrees, the average 3.0 degrees Celsius. In three of the five cases the difference was bigger than 3 degrees. According to the statistics on Ogimet Tsetsen Uul had only 8 cm of snow cover that time, while the researched basin had around 20 cm. In my opinion this could give an advantage of 1-2 degrees, but not above 3 degrees.

It can be noticed that the three bigger differences coincide with the three coldest measurements in the frost hollow, while the remaining two with less impressive discrepancies are the ones, when the cold was less severe. Tsetsen Uul’s lowest reading was also on 13th January, but was 3.5 degrees milder than in the high desert.

The most radical conclusion results from the comparison between the small hollow near my tent and the much bigger and deeper researched basin. It is true that it was only a single night, but as the two places are very close, the snow cover similar and the general conditions were characteristic, I am strongly inclined to believe that approximately the same thing would happen during any nights with good potential for strong thermal inversions. I also think that most of the same sized and shaped hollows (which are very common in this desert) will cool the same way as the observed one.

This case is especially interesting as the place is situated right on the saddle, not in an already cooled air mass as it would be somewhere inside the bigger basin’s endorheic sector. Most likely all that impressive “thermal plunge” came from the potential of the small scale topography. Beside these this hollow don’t even have a particularly good sky view factor, as a decent percentage of the slopes have the inclination above 20 degrees.

I have three main conclusions related to the above mentioned facts:

-First is that (regarding the drainage area) size doesn’t really matter at all.

-Second is that a 8-10 meters of depth is enough to approach the maximum potential of a frost hollow. The thermal drop will happen in a more abrupt way than in the deeper basins.

-Third is that relatively steep slopes are suitable (maybe even necessary?) for fast and efficient cold air pooling, despite the altered sky view factor.

As a summary this season was a modest one without a single really good night in the researched period, but the last one’s teaching compensated me for the lack of minuses. A return to the area (hopefully with all the necessary devices this time) is likely.