Intro: hot air, cold waters

Contrary to its name, The Caspian Sea actually is a huge lake, the biggest in the entire world, by far. While an enclosed body of water and mostly surrounded by arid land, its salinity is quite low on average, especially in the northern part where the inflow of the mighty Volga river dilutes it significantly. The surface of the lake lies 29 meters below the sea level and is joined by an extensive sub-sea level land area known as the Caspian Depression. Some isolated parts of this geomorphologically atypical structure descends even more, reaching the minimum of -134 meters in the Karagiye Depression, the lowest place in Kazakhstan and 5th in the world.

The city of Aktau lies on its coast in the north-eastern sector and is the capital of Mangystau district in western Kazakhstan. With modest cultural background and more pragmatic in existence, it’s a typical post-soviet industrial agglomeration based on oil, which by the way is the primary resource of the entire province. Despite this it definitely has its own specific “soul”, which can be defined as something between starkness, surreal and patches of modernity. The people are mostly kazakh, but you can see many others with russian features too. The tourism is in development, still mostly internal.

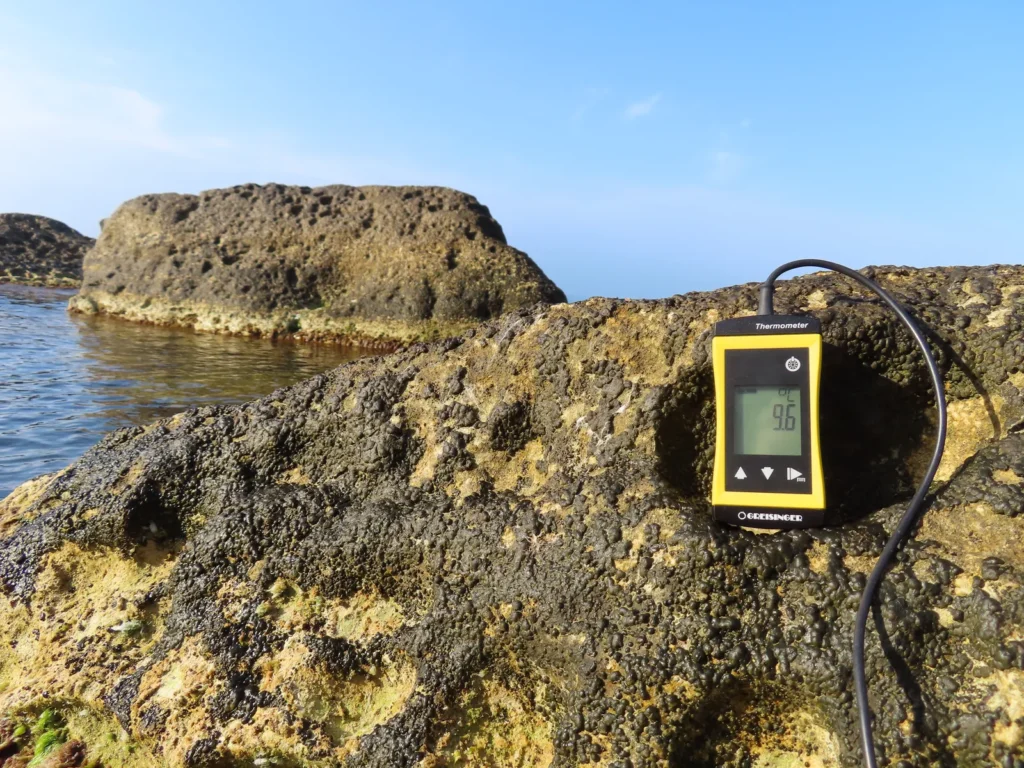

The climate of the fast growing medium sized (towards 300.000 inhabitants) port city is cold-semidesertic with mediterranean-like warm to hot, dry summers and moderately cold, also mostly dry winters with a few snowfall events annually. During the summer there is a characteristic, often shocking discrepancy between the hot desert air and the still much cooler seawater, which can sometimes exceed 20 degrees. In concrete details: air well above 30 degrees, seawater even below 10 degrees. The most likely explanation is cold upwelling caused by wind.

Choosing the target

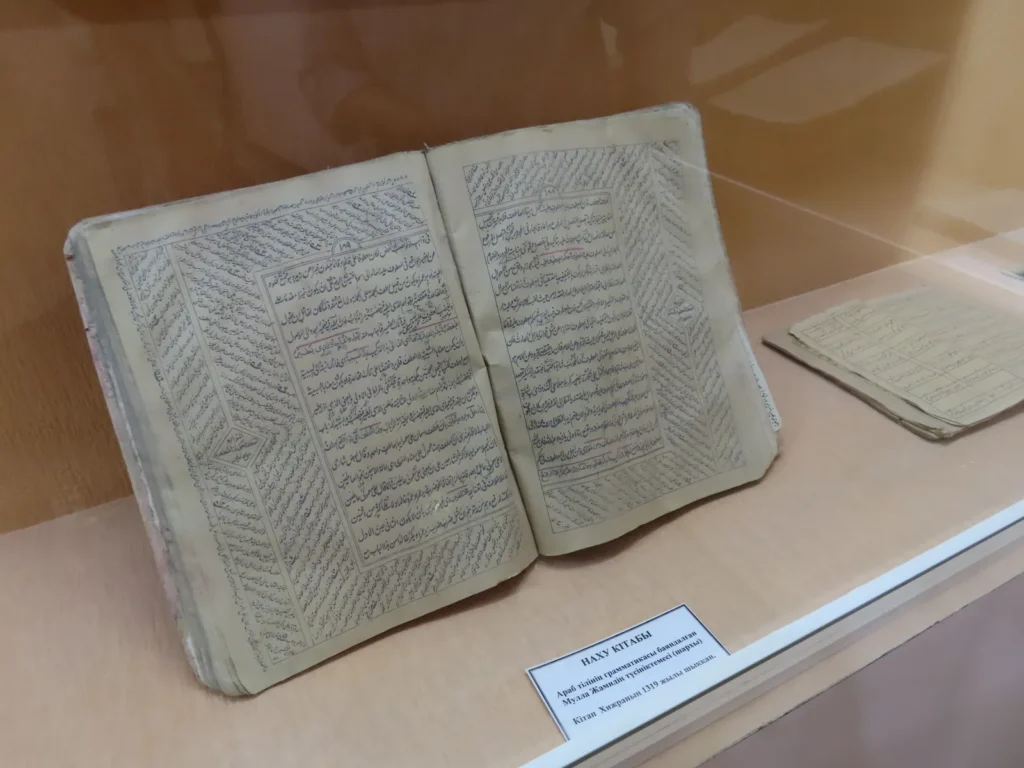

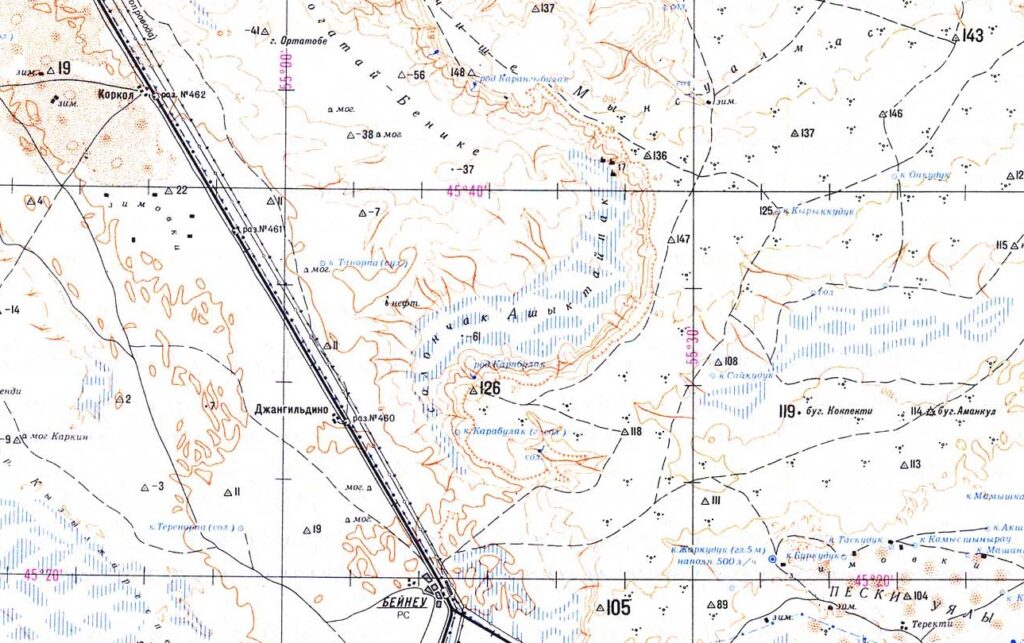

I was always fascinated by the parts of the land situated below the sea level, firstly because of the unusual, “inverted-mountain” topological anomaly. Then – unsurprisingly – I also correlated those locations with the extreme desert heat, encountering during my early intellectual pursuits places like the Dead Sea, Death Valley, Danakil and the Turpan Depression. While the mentioned attraction is general, I am the most fascinated by the least known examples of this already peripheral branch. And here we are: I chose a depression so little known, that is concretely mentioned only on detailed soviet topographic maps in Cyrillic.

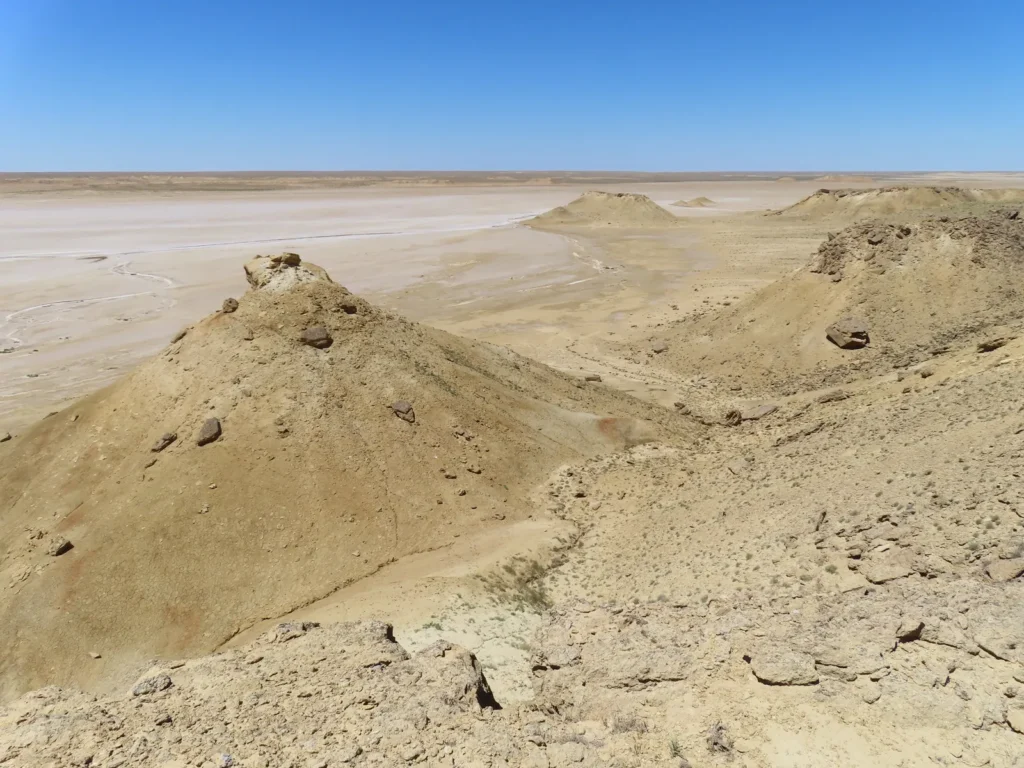

The name of the sunken basin is Ashyktaypak and it lies between the Caspian and Aral lakes at the foot of the northern Ustyurt Plateau, pretty far from civilization in every direction. The elevation of the salt flat lying on its bottom is -62 meters. Topographically and also genetically can be considered part of the bigger Caspian Depression, even if separated from it by a low ridge.

The closest inhabited place of considerable size is Beyneu, another fast-growing, oil based industrial settlement. While already well above 50.000 heads (some say 80.000) still maintained its old village status. Technically is the biggest village in Kazakhstan and is likely top-level even in the world chart. The raw geographical isolation is real, but the link with Aktau is decent, with daily connections both by railway and good, new asphalt road (470 km).

Beyneu itself lies barely above the sea level, on that flat, low ridge separating the Caspian and the Aral Sea mentioned earlier. The low elevation combined with the huge distance from the moderating effect of the oceans is responsible for the fact that the area is unusually hot in the summer compared to the relatively high latitude. Concretely, it lies slightly above 45 N, which means it’s already closer to the North Pole than to the Equator.

And this was the very thing why I chose this exact place to be the location of this year’s research: it probably has the hottest summers between all places situated closer to the Arctic than to the Tropics. Northern heat? Something like that.

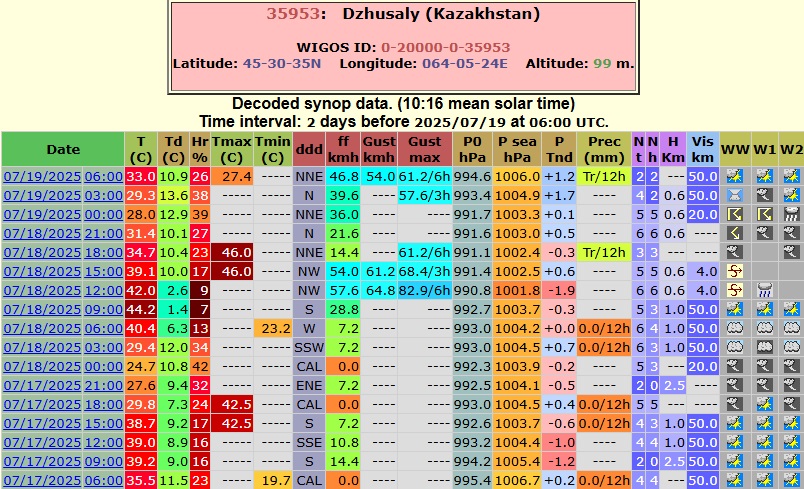

Translated to concrete numbers, Beyneu’s average maximum for July according to the available sources is around 35 centigrade, which is a solid base even in the hottest parts of Europe like Andalusia or the Peloponnese, both lying much more to the south, below 40 degrees latitude.

It’s absolute record (46.6 degrees) also mirrors the mediterranean maximum potential and beats most places in the entire world too if calculated to similar geographical latitudes, with a few isolated exceptions like Lytton in SW Canada or Steele in North Dakota (both exceeding 49 centigrade). But while in the latter spots the extreme heat is a much rarer guest (July average max temps between 27-30 degrees), Beyneu’s typical summer vibe is clearly on the tropical side.

Regarding the more fine-tuned details, inside the endorheic basin I strategically chose a semi-enclosed topographical structure of smaller scale with westerly exposure with the purpose to capture and reflect the afternoon insolation even more. It’s basically situated at the foot of the northern Ustyurt, a desertic plateau of marine origin, formerly covered by the ancient Tethys and Paratethys seas.

Brief summary of the research

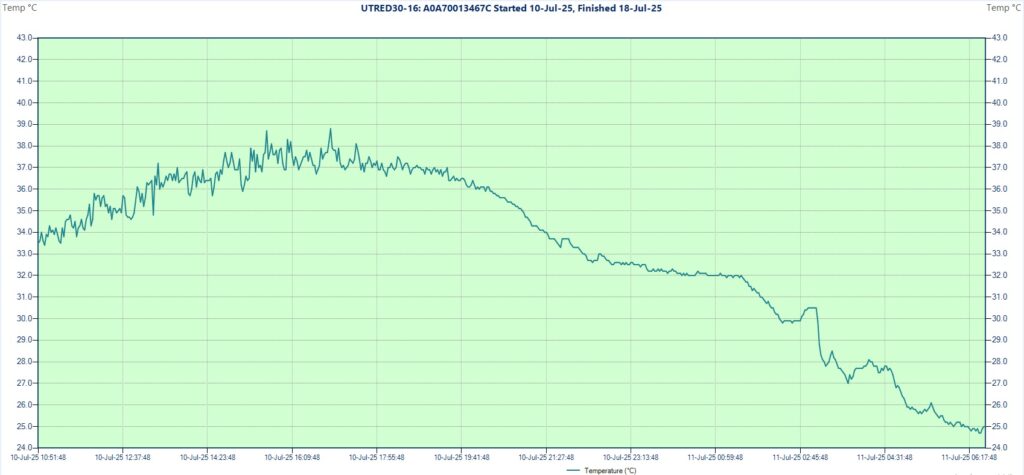

My flight landed in Aktau (via Istanbul) on 6th July in the late night. After a few days, during which I visited Saura oasis and the Golubaya bay on the Caspian coast north of the city, I moved to Beyneu by train, arriving there on 10th July in the morning. Already prepared, I instantly continued the journey by local minibus (marshrutka) to the nearby Sarga village, the closest settlement to my target.

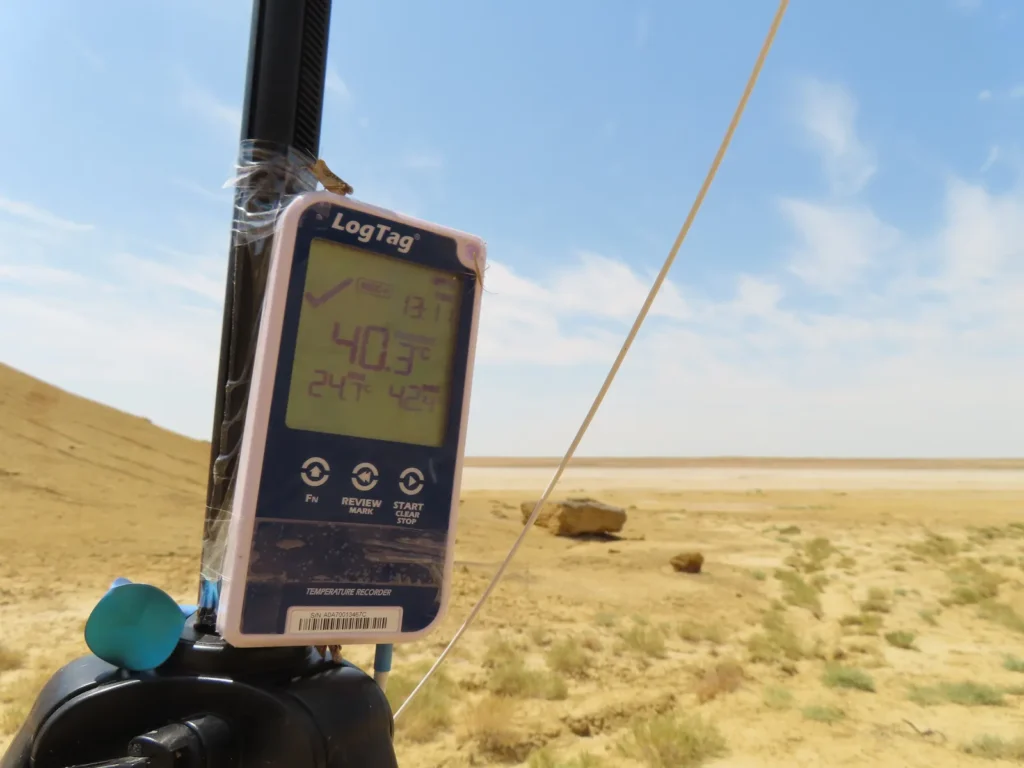

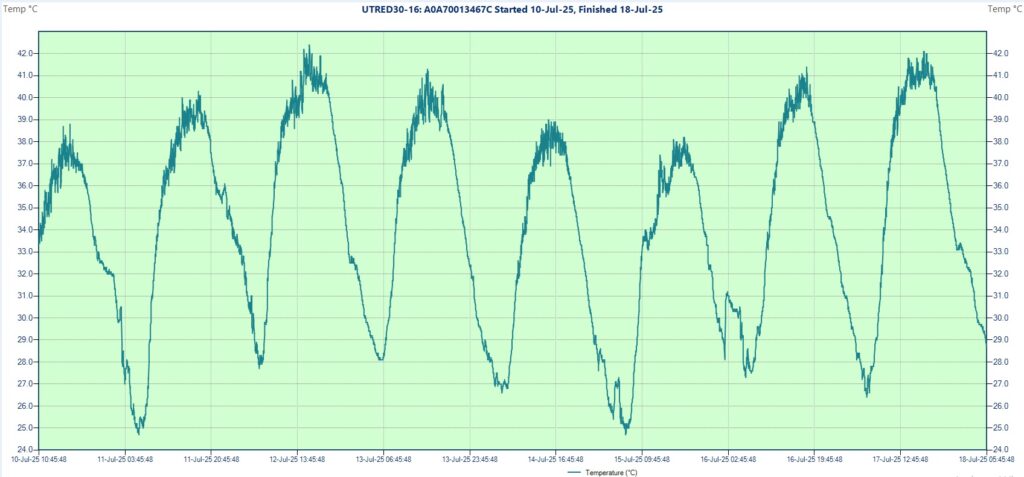

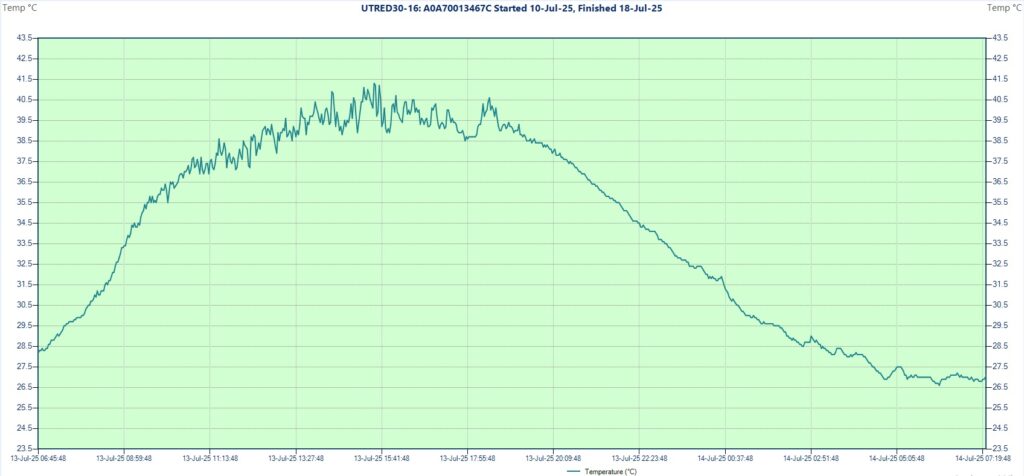

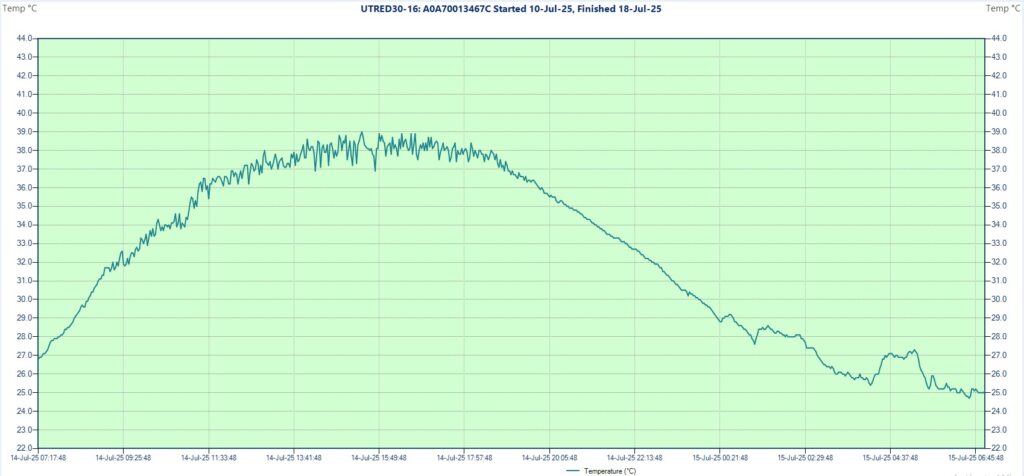

After a 10 km hike (around 2.5 hours) through the flat steppe, then the salt marsh, I reached the chosen location and soon installed the measuring equipment on the tripod. The logger started its operation at 10:46 AM showing 33.4 degrees as first reading.

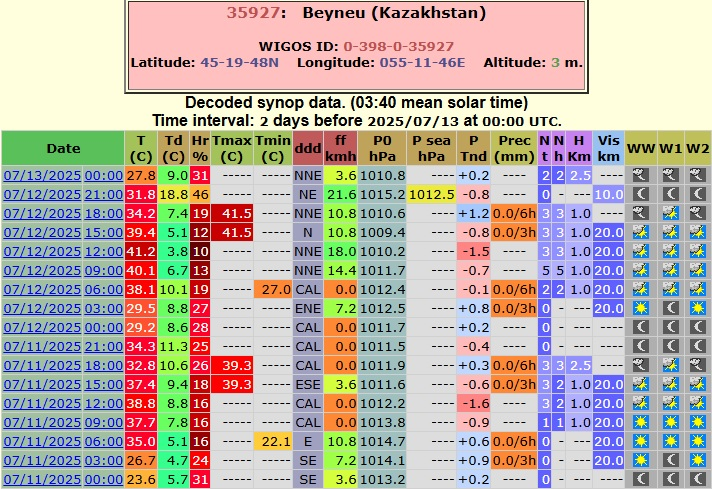

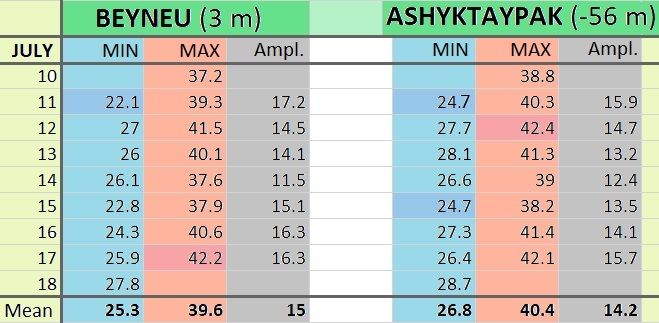

The sky was completely clear and it will remain like this the entire day. I stayed near the instrumentation checking the temperature values on the screen multiple times during the afternoon as usual. The maximum of the day reached 38.8 degrees around 5 PM.

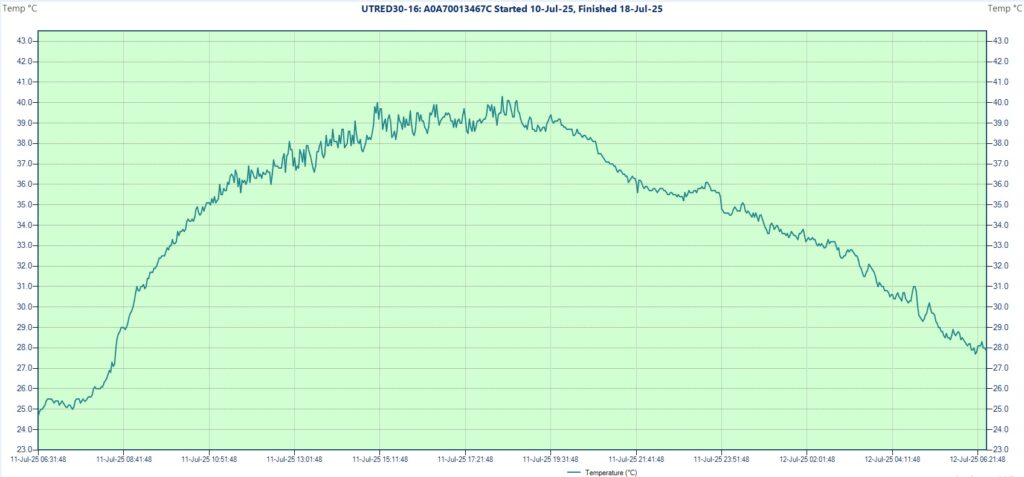

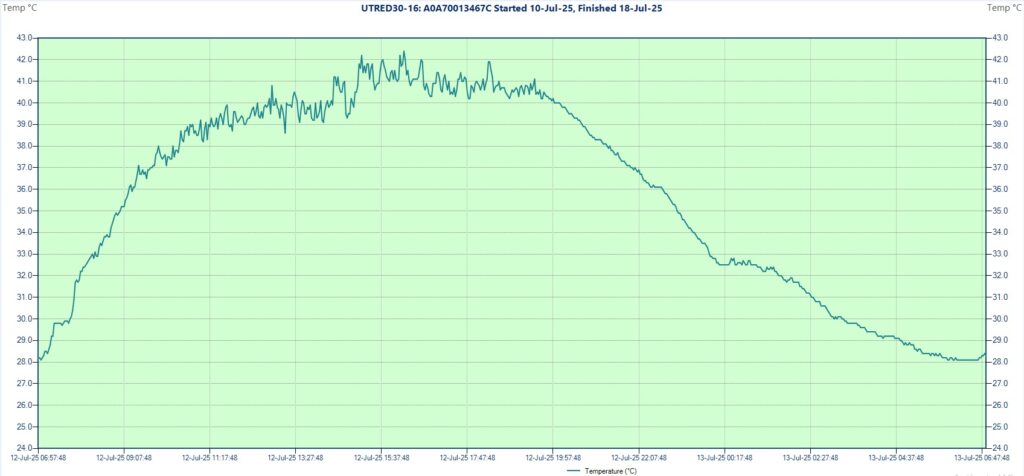

The next morning returned to Beyneu from where I came back for another field-trip on 13th July. Arriving at the camp I saw that on the previous day the temperature climbed to 42.4 degrees Celsius, which will remain the highest value of the entire research period. During this visit the daily max was 41.3 degrees (between 3-4 PM), while the sky became partially covered after 2 PM.

The third and last field-trip happened on 17th July, when I caught live 42.0 degrees around 6 PM, the hottest directly experienced weather during this expedition. Until around 1 PM it was full sunshine, then rapidly became cloudier, transforming into completely overcast in the mid-afternoon hours. Still the temperatures were maintained elevated with relatively small fluctuations even into the early evening hours.

Generally it was quite hot during a significant part of the researched days, often even the evenings remained above the human body temperature. Five out of eight cases the temperature climbed over 40 degrees and two times over 42 degrees, while in the coolest morning dropped to 24.7 degrees Celsius. The sky was variable, typically clearer in the morning until noon and more cloudy in the hottest afternoon hours (convection). The wind was light to moderate.

The depression itself always lacked any kind of human presence during my visits and this is likely a generality in the hot, dry summer period. Camels and horses grazed on the western side, while cattle and sheep a little closer to the village. Outside a few birds (small to medium size), insects (mostly grasshoppers) and a dead turtle I couldn’t spot any other wild animal in the whole perimeter.

The instruments used in the field

-One LogTag UTRED30-16 data logger with the measuring range between -40 and +99 degrees Celsius, an accuracy of 0.5 degrees Celsius and a resolution of 0.1 degrees Celsius

-One Greisinger G1710 thermometer with the measuring range between -70 and +250 degrees Celsius, an accuracy and resolution of 0.1 degrees, used for instant hand measurements

-One photo camera tripod serving as the support for the instruments

-One helical solar radiation shield from Barani Design Technologies: https://www.baranidesign.com/

To be continued…